![]()

| Norman Lear 1922-2023 |

|

![]()

As producer of All In The Family and other groundbreaking sitcoms, he

made Americans take a good, hard look at themselves -- and laugh.

By Tom Gliatto in People

![]() early a century ago, a boy named Norman Lear stood by a lake with his grandfather, tossing pebbles into the water. When the old man told Norman that every additional pebble raised the water level, Norman chucked in a rock. Well, he said, the lake looked just the same. No, the water was higher, his grandfather responded, adding, but "all you see is the ripple." Reflecting on this decades later, after he'd become one of the most powerful creative forces in TV history, Lear supplied a moral: When you measure how you yourself might have changed the world, "be satisfied with the ripples."

early a century ago, a boy named Norman Lear stood by a lake with his grandfather, tossing pebbles into the water. When the old man told Norman that every additional pebble raised the water level, Norman chucked in a rock. Well, he said, the lake looked just the same. No, the water was higher, his grandfather responded, adding, but "all you see is the ripple." Reflecting on this decades later, after he'd become one of the most powerful creative forces in TV history, Lear supplied a moral: When you measure how you yourself might have changed the world, "be satisfied with the ripples."

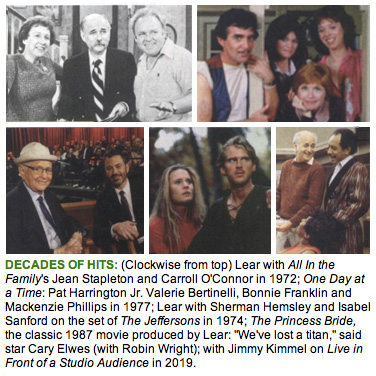

The venerated writer, who died at the age of 101 in Los Angeles on Dec. 5, redefined prime-time TV in the '70s as the creator and producer of landmark sitcoms (all on CBS) that showed audiences as an America that was complicated, diverse and troubled -- programs that took TV beyond what Lear called "tee-hee ha ha." All in the Family (1971-1979) introduced viewers to working-class bigot Archie Bunker (Carroll O'Connor).  That classic was spun off into two other groundbreakers: Maude (1972-1978) starred Bea Arthur as Archie's liberal cousin -- the first TV character to have an abortion -- while The Jeffersons (1975-1985) followed the upwardly mobile trajectory of George Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley), owner of a chain of dry cleaners. Lear kept pushing for new perspectives on One Day at a Time (1975-1984), about a divorced mother of two (Bonnie Franklin), and Good Times (1974-1979), centered on a Black family living in the Chicago housing projects.

That classic was spun off into two other groundbreakers: Maude (1972-1978) starred Bea Arthur as Archie's liberal cousin -- the first TV character to have an abortion -- while The Jeffersons (1975-1985) followed the upwardly mobile trajectory of George Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley), owner of a chain of dry cleaners. Lear kept pushing for new perspectives on One Day at a Time (1975-1984), about a divorced mother of two (Bonnie Franklin), and Good Times (1974-1979), centered on a Black family living in the Chicago housing projects.

"There's a Yiddish word that I sued for [Lear]," Rob Reiner, who played Archie Bunker's liberal son-in-law, told the Los Angeles Times. "Kochleffel, which is a ladle that stirs the pot.... He was fearless." Jimmie Walker, who played J.J. on Good Times, told People that Lear "stuck by his guns" when network executives advised caution. "We've gotten somewhere now. So that's his legacy."

If Lear loved to provoke audiences, his shows were also wonderfully funny. But what mattered most to Lear, who in 2000 bought one of the first published copies of the Declaration of Independence and toured it around the country, was that viewers could be brought together through laughter, whatever their differences. As he noted wryly, "There wasn't a single state that seceded from the Union" over his shows.

For Lear, there was also an odd tug of nostalgia in his fleet of sitcoms (at one point, he had 11 on the air): They reminded him of his childhood in New Haven, where family get-togethers -- noisy, angry affairs -- were also "a celebration of life." After serving in the Air Force during World War II, he headed to Hollywood and built a career writing comedy. He went on to win six Emmys overall (two in his late 90s) and was among the first inductees into the Television Hall of Fame in 1984.

Lear's best work still has the tang of relevance. One Day at a Time was rebooted for Netflix with a Cuban American mom (played by Justina Machado), and ABC's Live in Front of a Studio Audience specials introduced his hits to a new generation. Astoundingly vigorous, Lear never stopped juggling new projects. He insisted that TV shouldn't be afraid of advanced old age: "We all want to get there! It's good stuff. There's good stuff there." ![]()

| The Final Hours of John Lennon |

|

![]()

A new docuseries sheds light on a Beatle's tragic

death -- and the killer who ended the dream.

By Rachel DeSantis in People

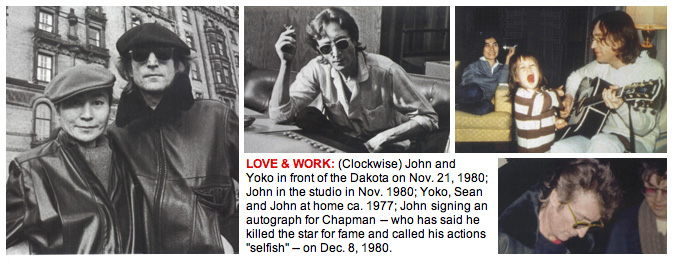

![]() he last time producer Jack Douglas saw John Lennon, the former Beatle was headed home after a hard day's work in the studio. He and his wife, Yoko Ono, had been at Record Plant in New York City, recording what would become Ono's 1981 single "Walking on Thin Ice," and Lennon smiled at Douglas as he went into the elevator. "He was very positive," Douglas recalls of the end of that session on Dec. 8, 1980. "They were both just so happy."

he last time producer Jack Douglas saw John Lennon, the former Beatle was headed home after a hard day's work in the studio. He and his wife, Yoko Ono, had been at Record Plant in New York City, recording what would become Ono's 1981 single "Walking on Thin Ice," and Lennon smiled at Douglas as he went into the elevator. "He was very positive," Douglas recalls of the end of that session on Dec. 8, 1980. "They were both just so happy."

It would be the last time Douglas saw his friend. As Lennon and Ono were about to enter the Dakota -- the building where they lived with their son Sean -- Lennon was shot and killed by Mark David Chapman, a young fan who'd sought the musician's autograph earlier that day. The shocking murder -- which is being reexamined in John Lennon: Murder Without a Trial, a three-part Apple TV+ documentary series that premiered on Dec. 6 -- brought a storied life to an abrupt end. "There's a lot more to the story than a lone gunman suddenly turns up, squeezes the trigger, end of story," says series director Nick Holt. "A lot of people obviously lost an idol, but first and foremost, very much [was] a dad and husband."

Just a month earlier Lennon had released Double Fantasy, a comeback album that was coproduced by Douglas and world go on to be a massive commercial success. "He didn't think we were going to set the world on fire with that record," says Douglas, who first befriended Lennon while engineering his landmark 1971 album Imagine. "But it didn't matter to him. He just wanted to tell the truth about where he was in his life at 40 years old. And he felt really good about it." Still, Douglas says, as Lennon plotted an upcoming tour and a possible Beatles reunion, he was plagued by unsettling premonitions: "He was plagued by unsettling premonitions: "He spoke about death every once in a while. He would say things like, 'I might be gone soon.' He would say, 'When I die, it's going to be bigger than Elvis.'"

Just a month earlier Lennon had released Double Fantasy, a comeback album that was coproduced by Douglas and world go on to be a massive commercial success. "He didn't think we were going to set the world on fire with that record," says Douglas, who first befriended Lennon while engineering his landmark 1971 album Imagine. "But it didn't matter to him. He just wanted to tell the truth about where he was in his life at 40 years old. And he felt really good about it." Still, Douglas says, as Lennon plotted an upcoming tour and a possible Beatles reunion, he was plagued by unsettling premonitions: "He was plagued by unsettling premonitions: "He spoke about death every once in a while. He would say things like, 'I might be gone soon.' He would say, 'When I die, it's going to be bigger than Elvis.'"

During that final session, Lennon told Douglas about an upcoming trip to Bermuda to recharge before continuing to work on new music. But he never made it to his 9 a.m. call time the next day. For former Dakota doorman Jay Hastings, who was working the night Chapman fired five shots at Lennon, the events play out in his mind "like it was yesterday," he says. "He came running up, and he's like 'I'm shot, I'm shot!' -- and he just ran past to the back office and collapsed." The star was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital, where he later died. Douglas and Ono had a private memorial service for John in the studio on Dec. 9. "That was the only service there was," he says.

Chapman, now 68, never stood trial. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in 1981, as his attorneys and prosecutors debated his mental state. Sentenced to 20 years to life in prison, Chapman was denied parole for the 12th time in 2022. Ono, now 90, lived in the Dakota until earlier this year, while Sean, 48, is a musician like his dad. "There were a lot of plans," says Douglas. "I once asked [John], 'What's your secret of writing a really great song? And he said, 'Tell the truth, and make it rhyme.' The reason why so many people felt close to him was because they always felt they knew him, because he sang about what he was going through. There was just this great truth about his music." ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.