![]()

| Remembering Rob Reiner |

|

![]()

The beloved actor-director left behind an incredible legacy from the 1970s to today.

By Eric Andersson in People

![]() s a director, Rob Reiner made the kinds of movies that became quotable classics, beloved across generations and watched time and time again. Among them: 1987's The Princess Bride, about a dashing pirate out to rescue his true love, and 1989's When Harry Met Sally...., the quintessential romantic comedy against which all others are inevitably measured.

s a director, Rob Reiner made the kinds of movies that became quotable classics, beloved across generations and watched time and time again. Among them: 1987's The Princess Bride, about a dashing pirate out to rescue his true love, and 1989's When Harry Met Sally...., the quintessential romantic comedy against which all others are inevitably measured.

The son of TV pioneer Carl Reiner (who created The Dick Van Dyke Show) and actress-singer Estelle Lebost, Rob was born in New York City in 1947. The family moved to Beverly Hills when Rob was 12, and after he attended UCLA, he followed his parents into show business.

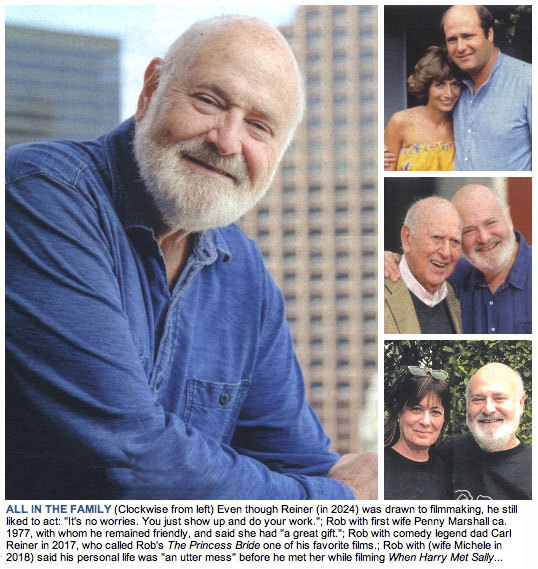

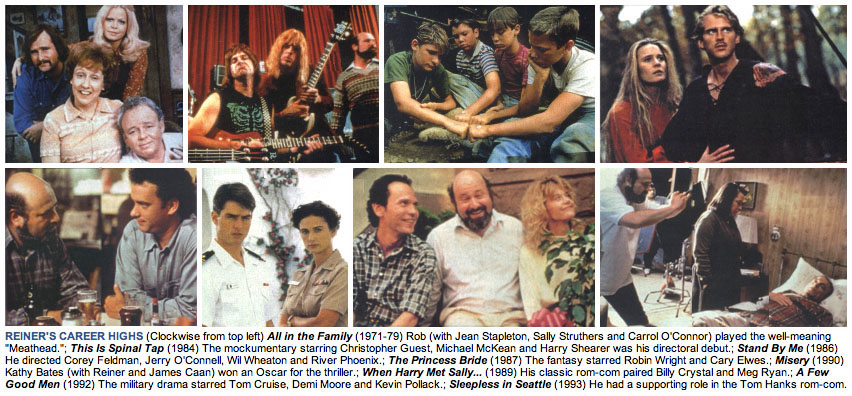

With an affable everyman look, Reiner landed small roles on shows like Batman and The Beverly Hillbillies but broke out as Michael Stivic -- aka Meathead -- in 1971 on the envelope-pushing sitcom All in the Family. (It was the same year he wed future Laverne & Shirley actress Penny Marshall.) Playing the liberal son-in-law of Carroll O'Connor's grumpy and bigoted Archie Bunker earned Rob two Emmys over eight seasons. "It was obviously a great show, and I loved doing it," he told People earlier in 2025, "but it was a stepping stone."

Indeed, Rob had wanted to direct since he was a teenager. On All in the Family, "I was looking at the other actors, where the cameras were," he said. "So it's not the best way to act. You're supposed to focus on what you're doing." When he left the show in 1978, Rob initially struggled to break into film. "At that time if you were in television, you were looked down upon by people in movies," he recalled. "They were royalty, and you were peons."

But Rob's persistence eventually paid off. His directorial debut, the 1984 mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap (which he also cowrote and costarred in), became a comedy cult classic. He went on to direct some of the most memorable films of the '80s and '90s (see below). While making When Harry Met Sally..., Rob, who had split from Marshall in 1981, was introduced to his future wife, Michelle Singer, a photographer who had stopped by the set. (She had snapped Donald Trump for the cover of his 1987 book Trump: The Art of the Deal.) "I look over, and I see this girl, and 'Whoo!' I was attracted immediately," he told The New York Times in 1989.

Rob's real-life love story inspired him to upend the original version for Billy Crystal's Harry (Rob was friends with Crystal for 50 years) and Meg Ryan's Sally, giving the characters a happy ending that wasn't in the initial script. "Originally Harry and Sally didn't get together. But then I met Michele, and I thought: 'Okay, I see how this works," he told The Guardian in 2018. (In the scrapped screenplay, "they meet again in New York, have a little conversation and walk in opposite directions," he told People.)

The couple collaborated at different times over the course of their marriage. Michele served as a producer on movies her husband made, including 2017's political journalism drama Shock and Awe and this year's sequel Spinal Tap II: The End Continues. Rob also credited Michele with inspiring his activism, like their work for marriage equality and universal access to preschool. "Basically, my wife made me a person," he quipped in 2010.

As the horrific news of the deaths of 78-year-old Rob and 70-year-old Michele at the hands of their troubled son Nick Reiner, 32, on Dec. 14 quickly spread through Hollywood, the Reiner family -- Rob and Michele were also parents to son Jake, 34, and Rob had a daughter Tracy, 61, from his first marriage to the late actor-director Marshall -- said in a statement they are "heartbroken by this sudden loss." Friends and loved ones across Hollywood struggled to make sense of the news as they paid tribute to the Reiners, both passionate civil rights advocates. "This is most tragic for two extraordinary people who gave so much to make this a better world," said Michael Douglas, who worked with Rob on the 1995 movie The American President. "Rob and Michele will be deeply missed." And Jerry O'Connell, who was just 11 when he costarred in Rob's 1986 movie Stand By Me, called the situation "devastating," adding about Rob, "I feel like a parent has passed. He was a special human being. A kind soul." ![]()

| Flashback to 1976! |

|

![]()

From People's Oct. 25, 1976 issue.

BEHIND THE CURTAIN OF HITMAKER STEVIE WONDER'S MUSICAL GENIUS

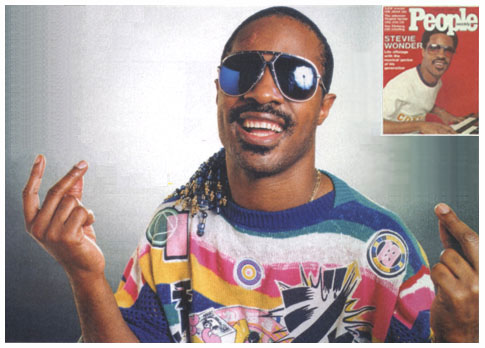

![]() n his relentless fashion, Stevie Wonder worked two torturous years on his new album Songs in the Key of Life. "Music can measure how broad our horizons are," he said. "My mind wants to see infinity." It took just one week to top the pop charts -- the first double LP (it has 21 cuts) ever to arrive in such a rush. The release was a year late, largely because of Stevie's perfectionism, but was released in time for 1976 Grammy eligibility. [The record went on to win album of the year.]

n his relentless fashion, Stevie Wonder worked two torturous years on his new album Songs in the Key of Life. "Music can measure how broad our horizons are," he said. "My mind wants to see infinity." It took just one week to top the pop charts -- the first double LP (it has 21 cuts) ever to arrive in such a rush. The release was a year late, largely because of Stevie's perfectionism, but was released in time for 1976 Grammy eligibility. [The record went on to win album of the year.]

Since his last musical outing Wonder, 26, welcomed daughter Aisha, 18 months, with his new lover Yolanda Simmons, 25. "I've always wanted to be a father," he says. "But I knew I had to wait till I met the right woman who would give my child the love it needs." Wonder adds, "I'd like 24 kids, a whole bunch, but I don't know if I'll ever make that." [He now has nine children.]

IN THE NEWS: OCT. 1976

Engagement: Elizabeth Taylor, 44, became engaged to her soon-to-be sixth husband, politician John Warner Jr., 49, after her second divorce from ex Richard Burton, 50, in July.

Health: Marty Feldman, 42, who is directing, writing and starring in The Last Remake of Beau Geste, leaves costars Ann-Margret, 35, Peter Ustinov, 55, and Michael York, 34, idle on the film's set after he comes down with a case of chickenpox.

Generational Talent: Ryan O'Neal (right) and his Oscar-winning daughter Tatum, 12, team up for a second time in Nickelodeon, a historical comedy costarring Burt Reynolds.

Turn On the Waterworks: Robert Hooks, Brenda Vaccaro, Joseph Cotten and Olivia de Havilland are drenched by 4,000 gallons of water in a plane crash scene for their upcoming movie Airport '77.

Bernadette's Burning Desire: "I want to do it all," says Bernadette Peters, now an Emmy, Grammy and Tony nominee, in a People profile. "Just point me in a direction I want to go, and I'm gone." ![]()

![]()

| The Best of EXTRA! |

|

![]()