![]()

| Confessions of a Rock and Roll Survivor |

|

![]()

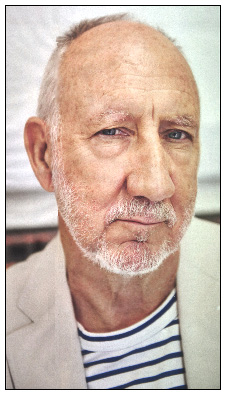

The Who's Pete Townshend gets candid about life, death and music.

By Rachel DeSantis in People

![]() e is the scribe behind the '60s battle cry "I hope I die before I get old" in the Who's classic "My Generation." Well, guitarist Pete Townshend turned 77 in May and has outlived two of his bandmates, but he still feels far from "old" -- especially when he's windmilling his way through 20-plus song set lists alongside the Who frontman Roger Daltrey. "When I was in my 60s, I would say, 'When I hit 70, I'm going to enter a period [called] the rage," he says over Zoom. "Maybe if I live to be 85, I'll do a bit of sailing or gardening, whatever it is that old people do. But my health is really good, so it's likely I'll die being hit on the head by something from a sailing boat." Here the rocker -- who unpacks the "most difficult" periods of his life in the new Audible Original Words + Music title Somebody Saved Me (out now) -- reflects on some of the tough challenges he's faced.

e is the scribe behind the '60s battle cry "I hope I die before I get old" in the Who's classic "My Generation." Well, guitarist Pete Townshend turned 77 in May and has outlived two of his bandmates, but he still feels far from "old" -- especially when he's windmilling his way through 20-plus song set lists alongside the Who frontman Roger Daltrey. "When I was in my 60s, I would say, 'When I hit 70, I'm going to enter a period [called] the rage," he says over Zoom. "Maybe if I live to be 85, I'll do a bit of sailing or gardening, whatever it is that old people do. But my health is really good, so it's likely I'll die being hit on the head by something from a sailing boat." Here the rocker -- who unpacks the "most difficult" periods of his life in the new Audible Original Words + Music title Somebody Saved Me (out now) -- reflects on some of the tough challenges he's faced.

Keith Moon, the Who's inimitable drummer, died of a drug overdose in 1978. What was the most difficult part of that time?

I tried everything. I tried giving him money, I tried starving him of money. I tried sending him into rehab. I tried sending him to a guru weirdo, voodoo doctors. I was obsessed with trying to keep Keith alive. It was quite clear that he was on a downward slide, and there was very little I could do. He was a very complicated character.

In 1979 a crowd surge before a Who show in Cincinnati killed 11 people. How did that affect you?

It's a form of post-traumatic stress, partly because we didn't witness what happened. We're going back to perform there soon for the first time ever since the tragedy, so it's an opportunity to reconnect. But it will open up old wounds. I've realized that there's nothing that you can do to change it. You just have to learn to live with it and try to accept that it happened.

You've been sober for almost 30 years. What has that journey been like?

What's interesting about alcohol, for anybody that regards themselves as an alcoholic, is that they found a medicine that works. For long periods, I was uncomfortable being in the Who. I wanted to be happily married and have a normal family and life, but it was proving to be impossible. Drinking helped me deal with it. Then one day it stopped working. I briefly tried a few other things -- cocaine, heroin -- but they didn't work. And then I tried sobriety. And sobriety is great, but you're living constantly with the fact that you don't have any medicine, and your makeup is that you're ill at ease with the world, ill at ease with life, ill at ease with what you do. What's so interesting about 12-step programs is this idea that there's a way you can manage one day at a time. It's a great philosophy, and it's helped me.

What does an ideal day look like to you now?

I'll sleep a long time, then get up and journal for about an hour and meditate for 20 minutes and stretch. Then I go and see my wife [musician Rachel Fuller, 48, whom he married in 2016] and say hello to the four dogs. We'll have lunch, and then I do a day's work in my studio. And in the evening, watch some TV and go to bed. It's a good day. ![]()

| A Comedic Voice for Generations |

|

![]()

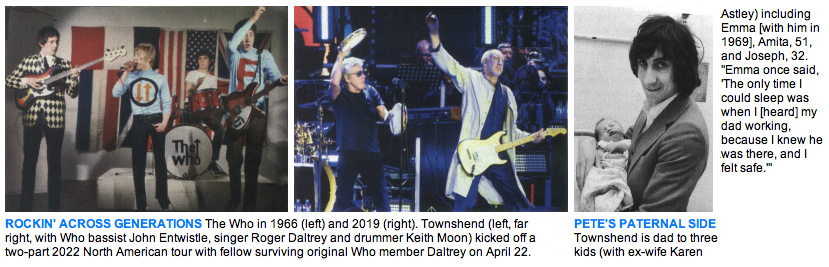

HBO premieres an homage to the eternally relevant, uniquely caustic comedian.

By Robert Edelstein in TV Guide

![]() n an HBO special in 1978, George Carlin reminded us that "They say the nicest things about you when you die; your popularity goes straight up. They'll even make stuff up if they have to: 'Well, he was a real a--hole, but he meant well.'"

n an HBO special in 1978, George Carlin reminded us that "They say the nicest things about you when you die; your popularity goes straight up. They'll even make stuff up if they have to: 'Well, he was a real a--hole, but he meant well.'"

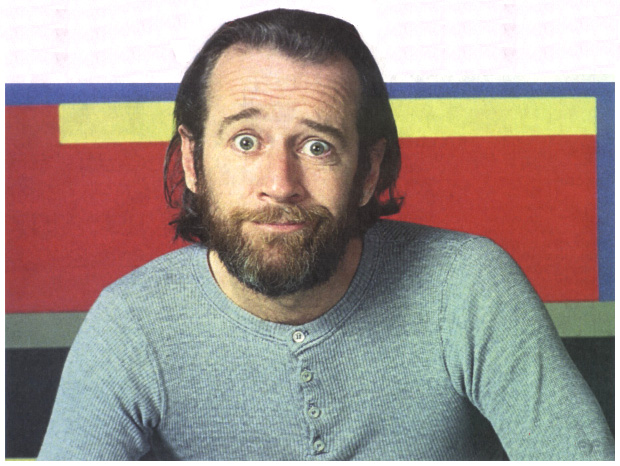

George Carlin's American Dream, premiering on that same network on May 20 and 21 at 8:00 p.m. Eastern/7:00 p.m. Central, is a two-part deep dive into Carlin's nearly 50-year-career in stand-up and proves he needs no such help. In the 14 years since his passing from heart failure at 71, his uniquely caustic perspective on life feels ever more relevant. "Every time something happens in the news, George Carlin's name starts trending on Twitter," says codirector Judd Apatow (The 40-Year-Old Virgin, The King of Staten Island). "And unlike most comedy, which doesn't age well, his material feels more prophetic and profound."

The great gift of American Dream is that it delves into the distinctly divided personal and professional sides of Carlin's life. As a comedian, the man who Apatow maintains "is on our Mount Rushmore" had at least four incarnations: tie-clad traditional joke teller; long-haired superstar class clown celebrant with a penchant for profanity (above, in 1975); the ultimate linguist who explored words and their meanings; and the angry old man who brought you face-to-face with heard truths. Meanwhile, he maintained a loving marriage to Brenda even as they dealt with addiction (alcohol for her, cocaine for him) and long separations.

The great gift of American Dream is that it delves into the distinctly divided personal and professional sides of Carlin's life. As a comedian, the man who Apatow maintains "is on our Mount Rushmore" had at least four incarnations: tie-clad traditional joke teller; long-haired superstar class clown celebrant with a penchant for profanity (above, in 1975); the ultimate linguist who explored words and their meanings; and the angry old man who brought you face-to-face with heard truths. Meanwhile, he maintained a loving marriage to Brenda even as they dealt with addiction (alcohol for her, cocaine for him) and long separations.

"The story is told through the eyes of his daughter, Kelly, who was very close with her father but also went through a harrowing childhood," Apatow says. "She became that voice." Carlin's insightful older brother Patrick, who died in April at 90, is also interviewed, as are fans like Jerry Seinfeld, Paul Reiser, Bill Burr, Jon Stewart, Bette Midler and Chris Rock.

In American Dream, Carlin is celebrated as the comedic voice for generations, fighting the Supreme Court over the "seven words you can't say on television" in the 1970s and helping kids find their way in life. "His comedy was important to me growing up," says Apatow. "In a way, it programs a young comedy person's mind about how to examine the world through this comedic lens. He was a lot of little kids' secret friend." ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.