![]()

| Gregg Allman: The Final Years |

|

![]()

Though he never got over the death of brother Duane, Gregg Allman sobered

up in the late Nineties and stumbled into redemption, of a sort.

By Mikal Gilmore in Rolling Stone

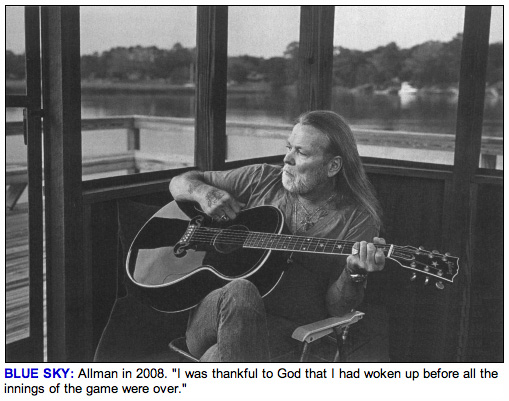

![]() regg Allman finally came face to face with his self-inflicted horror of drug and alcohol problems in January 1995 when the Allman Brothers Band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, on what should have been one of the best nights of his career. "I arrived in New York on Sunday," he recalled in his 2012 autobiography My Cross to Bear, got drunk, and stayed drunk for five days, including the induction ceremony itself." The evening of the 12th he appeared at the Waldorf-Astoria Grand Ballroom with other band members. "In the acceptance speech, I intended to say a bunch of things about my mother, and about [Fillmore manager] Bill Graham. But I just said, 'This is for my brother -- my mentor,' and then I split. Afterwards I looked at that footage, and I never took another drink. And I never will."

regg Allman finally came face to face with his self-inflicted horror of drug and alcohol problems in January 1995 when the Allman Brothers Band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, on what should have been one of the best nights of his career. "I arrived in New York on Sunday," he recalled in his 2012 autobiography My Cross to Bear, got drunk, and stayed drunk for five days, including the induction ceremony itself." The evening of the 12th he appeared at the Waldorf-Astoria Grand Ballroom with other band members. "In the acceptance speech, I intended to say a bunch of things about my mother, and about [Fillmore manager] Bill Graham. But I just said, 'This is for my brother -- my mentor,' and then I split. Afterwards I looked at that footage, and I never took another drink. And I never will."

That was perhaps a wishful exaggeration, but he was nevertheless determined to change. He hired in-home nurses who worked in 12-hour shifts to help him finally kick booze. In his book, Allman asked, "Did I get any positive anything out of all that? And you've got to admit to yourself, no, I didn't. You can see what happened and that by the grace of God, you finally quit before it killed you."

Allman's time in the lower depths was over; he had stumbled into redemption, of a sort. "[In the late Nineties]," he wrote, "I started wearing a cross, because I finally got some sort of spirituality. Until that point I'd always felt alone, and while sometimes I still get that way because I have a real phobia about being alone, at least now I can do something about it.... Now, if I'm having a problem, or something is keeping me from sleeping, I'll just lay there and not really pray so much as just meditate. I get real still and talk to the Man."

In October 2014, the Allman Brothers played their final shows at the Beacon in New York. In the years after Dickey Betts, who left the band in 2000 amid his own drinking problems and erratic performing behavior, the band made their last studio album -- 2003's Hittin' the Note, their most forceful work since At Fillmore East in 1971 -- and ended in top form. The band had final tragedy in store, though, when drummer Butch Trucks committed suicide early in 2017. "I've lost another brother, and it hurts beyond words," Allman said in a statement.

|

As he was healing, he began planning the album he would make with T Bone Burnett. Low Country Blues debuted at Number Five -- "the highest I'd ever been on the charts and the highest debut ever for a blues record, except for one by Eric Clapton, which is pretty good company," Allman wrote. It also received a Grammy nomination for Best Blues Album of 2011. Allman decided it was time to grow closer to his children. He had five, each with a different mother, and he married seven times. "Every woman I've ever had a relationship with has loved me for who they thought I was," he wrote in 2012. "Maybe they were in love with whatever was onstage, but when the lights are out and the sound goes off, you're left with this dude, and that's me. Obviously, that's the person they didn't get to know..." That same year, he announced his engagement to the woman who would become his seventh wife and remain by his side to the end: Shannon Williams, 40 years his junior. "This time," he said, "I am really in love."

Further reading on Super Seventies RockSite!: |

Allman still wanted to make music, and he recently finished a new album, Southern Blood. He recorded some of it at Muscle Shoals, where his brother Duane had played on legendary sessions. "I would say he knew for the last six months that he was getting toward the end of his life," Gregg's manager said, "and he became resolved and peaceful."

Gregg Allman died on May 27th, of complications from liver cancer. He'd gone through all the years of hell -- much of it his own making -- and found himself in a hard-earned place. "I sit here in my house in Savannah, look out over the water at the oaks, and know that I have a reason to live," he wrote during the last years of his life. "After all I've been through, I can't help but feel I've been redeemed, over and over. Sometimes I scratch my head about why, but the only answer I can come up with is that maybe I deserved it because I've brought a lot of happiness to people's hearts. I get letters by the week from people thanking me for my music, and you can almost see the tears on the paper. Not that this justifies anything I've done, or says that it's okay I got fucked up because I made a lot of people happy -- no way. One right doesn't snuff out a wrong. All I'm saying is that maybe God just needed me down here to make some folks happy. Maybe it's that simple. ![]()

His greatest songs of the '70s decade, in a 50-year career that redefined the blues.

by David Fricke

"Midnight Rider" (1970) Gregg's best-known song, written with road Robert Kim Payne, was not a hit for the Allmans; the single never charted. But Gregg's portrait of outlaw nobility and escape became Southern rock's defining anthem, while the original recording on 1970's Idlewild South remains a perfect summing of the blues, country and soul that ran like a single river in that voice.

"Midnight Rider" (1970) Gregg's best-known song, written with road Robert Kim Payne, was not a hit for the Allmans; the single never charted. But Gregg's portrait of outlaw nobility and escape became Southern rock's defining anthem, while the original recording on 1970's Idlewild South remains a perfect summing of the blues, country and soul that ran like a single river in that voice.

"Statesboro Blues" (1971) The Allmans' immortal treatment, on 1971's At Fillmore East, of Blind Willie McTell's 1928 blues was rightly ranked at Number Nine by Rolling Stone in a 2008 list of "The 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time." But it would have only been a dynamite future-blues instrumental without Gregg's torrid howl.

"Whipping Post" (1971) It was easy to forget amid the luminous turbulence onstage, defined on record by the extended improvising ascension on Fillmore East, but the Allmans' signature jam also had a great song at either end: Gregg's vivid portrait of a man bound and bloodied by a woman's betrayal, sung in despairing crescendos and death-bed moans.

"Wasted Words" (1973) Reeling again from sudden loss -- bassist Berry Oakley's death in late 1972 -- the Allmans pressed on with defiant vigor, opening 1973's Brothers and Sisters with Gregg's rowdy challenge to judgement ("I ain't no saint, and you sure as hell ain't no savior"), armed with Dickey Betts' silver-snake slide guitar and new member Chuck Leavell's saloon-ruckus piano.

"These Days" (1973) For a time, during his Hour Glass days in Los Angeles, Gregg roomed with a young songwriter named Jackson Browne. On Laid Back, Gregg's late-1973 solo debut, he turned to this Browne song of painful confession and healing reflection, covering it with a compelling despair and autobiographical need.

"Brightest Smile in Town" (1977) Gregg's 1977 solo album, Playin' Up a Storm, was woefully mistitled, an underwhelming artifact made in the thick of personal turmoil and his band's disintegration. Ironically, Gregg found renewed vocal strength and inspiration in this 1963 Ray Charles gem, a song about bottoming out delivered like precious refuge.

| Resurrecting The Dead |

|

![]()

Rock's grooviest road warriors headline 'Long Strange Trip', an

epic new documentary from exec producer Martin Scorsese.

By Eric Renner Brown in Entertainment Weekly

![]() fter 50 years, more than 2,300 concerts, and no shortage of chronicles -- both the kind you read and the kind you watch -- what is left to say about the Grateful Dead? Plenty, it turns out. In Long Strange Trip, the new Amazon documentary executive-produced by Martin Scorsese, director Amir Bar-Lev (Happy Valley) depicts the psychedelic pioneers in vivid, often riveting detail. Clocking in at four hours -- a daunting run time that channels the band's fabled live shows -- the film, like the Dead themselves, demands total commitment, and it rewards those who hop aboard for the ride.

fter 50 years, more than 2,300 concerts, and no shortage of chronicles -- both the kind you read and the kind you watch -- what is left to say about the Grateful Dead? Plenty, it turns out. In Long Strange Trip, the new Amazon documentary executive-produced by Martin Scorsese, director Amir Bar-Lev (Happy Valley) depicts the psychedelic pioneers in vivid, often riveting detail. Clocking in at four hours -- a daunting run time that channels the band's fabled live shows -- the film, like the Dead themselves, demands total commitment, and it rewards those who hop aboard for the ride.

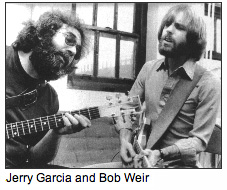

Don't fear, neophytes: The doc provides plenty of context as it runs through the band's history, from their jug-band roots to their Haight-Ashbury hippie days to stadium stardom. But the film still offers lots for Deadheads, and the extensive length allows Long Strange Trip to get pretty far-out. Major band members are interviewed, including the late Jerry Garcia, whose archival clips prove a major narrative force. Bar-Lev also scores top-notch stories from longtime roadie Steve Parish, colorful '70s tour manager Sam Cutler, celebrity Deadhead Sen. Al Franken, and more. He even tracks down reclusive lyricist Robert Hunter for a brief encounter that's one of the film's funniest moments.

Naturally, the film incorporates plenty of stellar Dead recordings, from acid-soaked '60s jams to their 1987 top 10 hit "Touch of Grey." (The soundtrack is being released simultaneously too.) Bar-Lev's tendency to reduce lengthy musical improvisations to bite-size nuggets can frustrate, but certain archival clips astound: Rehearsal footage of Garcia and bandmates Bob Weir and Phil Lesh workshopping harmonies for 1970's "Candyman" is pure Dead nirvana. The doc's momentum ebbs and flows, but that rhythm will feel right-on to anyone who ever saw the Dead perform. It's all about finding the gems, and Long Strange Trip is a treasure chest. B+ ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.