![]()

| 'House' Call |

|

![]()

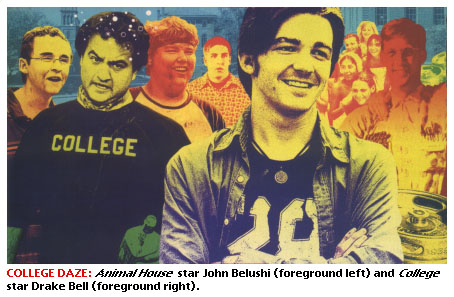

Thirty years after 'Animal House,' the latest college comedy is an orgy of the boring.

by Owen Gleiberman in Entertainment Weekly

College

Starring Drake Bell, Andrew Caldwell

Directed by Deb Hagan

R, 95 mins.

![]() he brainless, cardboard new movie College will get its dismal due later -- much later -- in this piece. For now, though, I'd like to focus on a thought I had while sitting through this tedious campus romp: What's the most influential blockbuster of the last 35 years? Sure, no question, it's Jaws or Star Wars. But what I really mean is: Which movie of the last 35 years has had the most influence not just on other movies but on America itself? What comedy whoopee-cushioned the cultural DNA, putting its scuzzy, trash-the-barricades stamp on life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? I'd argue that that movie is National Lampoon's Animal House.

he brainless, cardboard new movie College will get its dismal due later -- much later -- in this piece. For now, though, I'd like to focus on a thought I had while sitting through this tedious campus romp: What's the most influential blockbuster of the last 35 years? Sure, no question, it's Jaws or Star Wars. But what I really mean is: Which movie of the last 35 years has had the most influence not just on other movies but on America itself? What comedy whoopee-cushioned the cultural DNA, putting its scuzzy, trash-the-barricades stamp on life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? I'd argue that that movie is National Lampoon's Animal House.

Thirty summers ago, on July 28, 1978, Animal House first foam-blasted its way onto movie screens. It was an instant smash, which meant that a little over a month later, just as the fall college semester was settling in, a whole generation was primed for the Don't worry, just party! revolution. Animal House kicked off a frenzy of frat-house pledges, turning the toga party into the collegiate beer-slurp bacchanal of choice. But it wasn't just the cheesy ripped-sheet Roman costumes, or the sudden obsession with songs like "Shout." It wasn't just Greek chic. Set in 1962, which allowed it, in essence, to turn American Graffiti into a comic book, Animal House took place before the dawn of the hippie '60s, but in spirit it was about what happened after the '60s.

|

Even the flatness of the characters became part of the movie's appeal. Tim Matheson, as Otter, had all the charm of a junior Tucker Carlson, and Tom Hulce's Pinto was just a sweet doofus, but it's precisely because the Deltas (except for Bluto) were such B-movie blanks that they could embrace campus rebellion by becoming part of a mob. Animal House helped kick off the Reagan era by turning anarchy into conformity (and vice versa). Maybe that's why it's been with us ever since.

The movie's fusion of slob comedy and nose-thumbing, its celebration of smart stupidity, has proven infinitely adaptable. In Porky's (1982), the Animal House formula was nudged into soft porn, prefiguring a youth culture that would make leering online voyeurism hip. With Revenge of the Nerds (1984), it spawned the first comedy in which the heroes were computer geeks. Starting the next decade, in American Pie (1999) and its sequels, the sheer rabid horniness of Animal House returned as...sheer rabid horniness. And this summer (2008), the Delta mystique has come back again, first in The House Bunny, which gave it a delightful sex-positive feminist makeover, then in College, in which three high school seniors -- a shy normal guy (Drake Bell), a motormouth fatty (Andrew Caldwell) who spews his every porno thought, and a geek virgin (Kevin Covais) -- spend a weekend crashing frat parties at Fieldmont University. College is Animal House crossed with a dumbed-down Superbad; it musters no energy, even as nostalgia. But maybe that's because in Animal House, there was a real institution to rebel against -- it was called college -- whereas here, the frat house has become the institution. The characters go through the time-honored rites of hedonism, humiliation, and revenge as dutifully as if they were applying for their first corporate jobs.

College will be forgotten in three weeks, but Animal House lingers, and not just for the food fight, sorority peep show, or trashed parade. Three decades later, it can seem a strangely reactionary movie. There's that one shocking, racist moment when Pinto, seated nervously in a black bar, asks his date her major, and she replies, "Primitive cultures" -- at which point director John Landis cuts to the pomaded R&B band Otis Day and the Knights. (Horrible! How did they ever get away with it?) The entire movie remains, on some level, a celebration of privilege, its message being: If you go to the right school and dare to go crazy enough, have no fear -- you will come out okay. Then again, that's a message a lot of people, over the years, have believed and proven true. College, C- ![]()

| Back on the Bayou |

|

![]()

Four just reissued CCR classics show how these California boys

sidestepped the Summer of Love and reinvented Southern gothic.

by Barry Walters in Rolling Stone

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Bayou Country (1969)

Green River (1969)

Willy and the Poor Boys (1969)

Cosmo's Factory (1970)

(Fantasy)

Rock

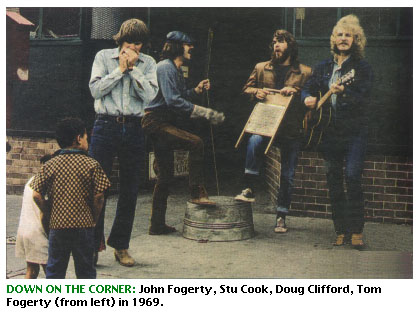

![]() ailing from El Cerrito, California, Creedence Clearwater Revival should've logically been another hippie collective waving flowers in neighboring San Francisco. As these 40th-anniversary editions suggest, leader John Fogerty instead invented an alternate identity for his band based on its otherwise unremarkable 1968 debut album's rumbling reinvention of a rock oldie.

ailing from El Cerrito, California, Creedence Clearwater Revival should've logically been another hippie collective waving flowers in neighboring San Francisco. As these 40th-anniversary editions suggest, leader John Fogerty instead invented an alternate identity for his band based on its otherwise unremarkable 1968 debut album's rumbling reinvention of a rock oldie.  His singing voice swollen with the exaggerated vowels and slurred consonants of shouting Southern bluesmen. Fogerty discovered his songwriting voice on 1969's auspicious Bayou Country when he further explored the Louisiana roots of CCR's hit "Suzie Q" cover. He wasn't, as his song proclaimed, "born on the bayou." But he could still conjure a Cajun swamp with a thick and steamy tangle of guitars for the instant classic "Proud Mary."

His singing voice swollen with the exaggerated vowels and slurred consonants of shouting Southern bluesmen. Fogerty discovered his songwriting voice on 1969's auspicious Bayou Country when he further explored the Louisiana roots of CCR's hit "Suzie Q" cover. He wasn't, as his song proclaimed, "born on the bayou." But he could still conjure a Cajun swamp with a thick and steamy tangle of guitars for the instant classic "Proud Mary."

The band's most sustained achievement, 1969's Green River, plays to these imagined Southern-gothic strengths. The title-track boogie offers an oasis of bucolic childhood memories to hide in when "the world is smolderin'." That's also the state of affairs in "Bad Moon Rising," which wraps a blithe rockabilly swing around a soothsayer's ominous vision of oncoming apocalypse. "Hope you are quite prepared to die" might be the most confrontational Vietnam War-era lyric to ever charm AM radio.

The band's most sustained achievement, 1969's Green River, plays to these imagined Southern-gothic strengths. The title-track boogie offers an oasis of bucolic childhood memories to hide in when "the world is smolderin'." That's also the state of affairs in "Bad Moon Rising," which wraps a blithe rockabilly swing around a soothsayer's ominous vision of oncoming apocalypse. "Hope you are quite prepared to die" might be the most confrontational Vietnam War-era lyric to ever charm AM radio.

The quartet's relatively relaxed fourth album, 1969's Willy and the Poor Boys, nevertheless upped the anger ante on "Fortunate Son," which rages against class-based draft inequality with rare, beat-driven fury: Even Dylan couldn't pen a protest song that makes you wanna dance. CCR's commercial apex, 1970's Cosmo's Factory, stacked Fogerty's peak songwriting streak -- check the particularly stellar storybook whimsy of "Lookin' Out My Back Door" -- against divergent Motown, Sun Records and Bo Diddley roots tributes that all proved the same point: CCR blended anxious soul rhythms with loose country twang to embody a haunted but harmonious America. But it couldn't last. Their guitarist, John's brother Tom Fogerty, split after the recording of 1970's uneven Pendulum, and the rest soon unraveled -- not even John could ever regain CCR's telepathic groove. Unfinished demos and ragged live cuts scattered across these reissues similarly add little to the group's legacy: Hammering out six albums in three years, Creedence couldn't afford to shelve anything worthy. Bayou Country * * * 1/2; Green River * * * * *; Willy and the Poor Boys * * * *; Cosmo's Factory * * * * 1/2

The quartet's relatively relaxed fourth album, 1969's Willy and the Poor Boys, nevertheless upped the anger ante on "Fortunate Son," which rages against class-based draft inequality with rare, beat-driven fury: Even Dylan couldn't pen a protest song that makes you wanna dance. CCR's commercial apex, 1970's Cosmo's Factory, stacked Fogerty's peak songwriting streak -- check the particularly stellar storybook whimsy of "Lookin' Out My Back Door" -- against divergent Motown, Sun Records and Bo Diddley roots tributes that all proved the same point: CCR blended anxious soul rhythms with loose country twang to embody a haunted but harmonious America. But it couldn't last. Their guitarist, John's brother Tom Fogerty, split after the recording of 1970's uneven Pendulum, and the rest soon unraveled -- not even John could ever regain CCR's telepathic groove. Unfinished demos and ragged live cuts scattered across these reissues similarly add little to the group's legacy: Hammering out six albums in three years, Creedence couldn't afford to shelve anything worthy. Bayou Country * * * 1/2; Green River * * * * *; Willy and the Poor Boys * * * *; Cosmo's Factory * * * * 1/2 ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.