![]()

|

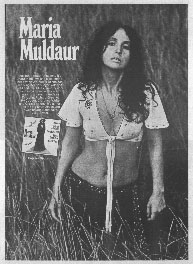

Maria Muldaur

Reprise MS 2148

Released: August 1973

Chart Peak: #3

Weeks Charted: 56

Certified Gold: 5/13/74

This is it: One of the half-dozen best albums of the year, the kind of glorious breakthrough that reminds me why I fell in love with rock & roll -- even though there isn't much straight rock here. Maria Mulduar's art is mature, sophisticated, sensual and wise. She moves among the genres of jazz, Dixieland, jug band, country, pop and rock (blues are inexplicably missing) as if they were flowers in a garden, each worthy of her tenderest loving care. She handles humor with an earnest undercurrent, seriousness with a sense of necessary detachment, pain with an openness that elevates rather than diminishes, and musical styles with a precision that is the product of years of patient hard work and study.

This is it: One of the half-dozen best albums of the year, the kind of glorious breakthrough that reminds me why I fell in love with rock & roll -- even though there isn't much straight rock here. Maria Mulduar's art is mature, sophisticated, sensual and wise. She moves among the genres of jazz, Dixieland, jug band, country, pop and rock (blues are inexplicably missing) as if they were flowers in a garden, each worthy of her tenderest loving care. She handles humor with an earnest undercurrent, seriousness with a sense of necessary detachment, pain with an openness that elevates rather than diminishes, and musical styles with a precision that is the product of years of patient hard work and study.

The material (drawn from both contemporary and standard works) revolves around either historical themes or assumed personal autobiographies. As a whole the album looks to the past as a source of strength to face the present. Consequently, Maria sidesteps the easy trap of campiness -- which is as far from her style as the overt assault on a lyric of an R&B singer -- and substitutes an affection and affinity so deep that she creates an immutable link between past and present, the artist and her art.

Click image for larger view. |

And on Maria Muldaur she has the help of producers (Joe Boyd, with whom she has worked before, and Lenny Waronker) and session men (including Ry Cooder, Jim Keltner, Chris Ethridge, Mac Rebennack, his drummer John Bourdreaux, Richard Greene, Clarence White, Amos Garrett, Tonight Show drummer Ed Shaughnessey, and pop traditionalist arranger Nick DeCaro) sufficiently sympathetic to her emotional and musical range. The personnel continually varies to suit the shifting moods of the album's 11 cuts, and it is another proof of her strength that she dominates such prodigious talent with ease.

The record is organized around clusters of material -- some Dixie-arranged tunes, a couple of jazz-and-pop numbers, string-dominated straight pop songs, and then some climactic contemporary original material by two new songwriters, Wendy Waldman and the Cambridge-based Kate McGarrigle. As an example of the first-mentioned style, she delivers Jimmie Rodgers' "Any Old Time" with near supperclub sophistication while surrendering none of the song's humor. She does more than that for Doctor John's "Three Dollar Bill," a hilarious trifle she dignifies with a graceful delivery, where a lesser artist would have reached for a lusty growl. "Don't You Feel My Leg" is New Orleans porno and has a static arrangement, but Maria maintains her ineffable ability to balance conflicting emotions, in this case, desire and melancholy.

"Midnight at the Oasis" and Dan Hicks's "Walking One and Only" move the album into a jazz-pop feeling, and we are again aware of what she avoids: Maria doesn't bowl us over with a complexity and skill of her technique, nor proclaim the sophistication of the arrangements, nor compromise the material to make it more generally appealing. As a singer her sense of irony is as profound as Randy Newman's is as a writer, and she holds "Midnight" together by walking a tightrope -- singing its crazy lyrics deadpan. She also wraps her voice around a mind-shattering guitar solo from master Amos Garrett. (His work here is only a notch short of his spot on her earlier recording of "Georgia on My Mind." Woodstock legend has it that J. Robbie Robertson put that performance on a tape loop so he could listen to it continuously.) Meanwhile, on "Walking" Maria steps out, pushing the distiguished Messrs. Shaughnessey and bassist Roy Brown into place while Richard Greene reminds us how he got his reputation for fiddle playing. Maria does all the voices, and I don't miss the Pointer Sisters.

With so much fine root material I was surprised that my favorite cuts are all recently composed. Wendy Waldman's "Vaudeville Man" is in the Dixie vein but with a richly melodious chorus. The track sports Bill Keith's superb banjo, Andy Gold's oh-so-pretty finger-picked guitar, a horn arrangement by The Doctor that punctuates the verses with soul riffs, and the chorus with easy-on-the-ears whole notes.

The last song on either side clinches the album -- they will reach you if nothing else does. Kate McGarrigle's "The Work Song" is about plantation life, the birth of black music and a lot of other things, and fuses hilarious verses with a powerfully righteous chorus. It would be easy for the artist to play the former for laughs and the latter for tears, but Maria sings it all with tremendous sincerity, lending a nearly tragic quality to the funniest lines and a feeling of gaiety to the most militant. Hence, her reading of the following is remarkably ambiguous,

Back before the blues were blues,

When the good old songs were new

Songs that may no longer please us

'Bout the darkies, A-bout Jesus

Mississippi minstrels, the color of molasses,

Strumming on their banjos to entertain their massahs,

Some said garbage, some said art

You couldn't call it soul,

You had to call it heart

while she enlivens the following with her greatest display of warmth:

Backs broke bending digging holes to plant the seeds,

The owners ate the cane and the workers ate the weeds.

Put mud in the stove and water in the cup,

You work so hard you died standing up.

At the conclusion of this utterly magnificent performance I don't know whether to laugh or cry. She has grasped some irreducible, cosmic feeling for America reminiscent of the force of Bob Dylan's "It's Alright, Ma," Randy Newman's "God's Song," and Robbie Robertson's "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" and "King Harvest."

If "The Work Song" stands as her most grandiose effort, the final cut, Wendy Waldman's "Mad Mad Me," stands as her simplest and most frightening. This eloquent statement about the existence of redemptive pain, suffering and love is the perfect conclusion to a melancholy, controlled and complex album. Ms. Muldaur's vocal iciness is integral to its effectiveness; if she merely sang it with abandon the shock would be too much to withstand.

She is aided by Greg Prestopino's deliberately simple, shattering piano (an exceptional singer, he will be heard from again in his own right) and a small-scaled string arrangement. But the album's greatest moment belongs to her alone. She avoids self-pity in the face of inevitable and irreversible tragedy and converts sorrow into strength, compressing into two minutes and 45 seconds a level of intensity that stretches capacity for understanding. Intensity and pride -- for beneath the sadness I glimpse a sense of satisfaction in her own triumphs, both personal and musical: After a decade of work, she has this masterpiece to show for it and she somehow seems to know it. Long after Maria Muldaur ends, I can still hear her final, tense, perfect wedding of voice and lyrics, "Oh, baby, how I love you, mad as I think you are/Guess you think I'm crazy too, but mad mad me, I love you." Listen to it -- it may haunt you too.

- Jon Landau, Rolling Stone, 10/27/73.

Bonus Reviews!

Maria Muldaur, late of Kweskin's Jug Band and late of two very good albums with her husband Geoff, makes her solo bow on an album that never seems to make up its mind. Her previous work has always been eclectic in style and performance, but there it becomes unfocused and jumbled. She is very talented, strikingly so in such comedy songs as "Don't You Feel My Leg (Don't You Make Me High)," in which her slightly disheveled soprano is used to raffish effect, and "Three Dollar Bill," a tirade along the lines of the classic "Why Don't You Do Right?" But what to say of her performance in Dolly Parton's "My Tennessee Home," where she sounds like Stella Dallas confiding to a tea-leaf reader, or in a couple of drooping Wendy Waldman clinkers? Only that Muldaur becomes indistinguishable from hundreds of others out there in Sensitivityland. That the surrounding production is consistently grand and garish is no help at all.

Real coarse of me, I know, to like only them knee slappers that she sings so good. But I never could make much out of them soap operas.

- Peter Reilly, Stereo Review, 3/74.

My favorite sleeper of 1973 is about to break into the Top Ten. Since its release eight months ago, Maria Muldaur tirelessly has worked the clubs and second bills of concerts in every part of the country. Her album has become an FM staple and grown steadily outward from its original status as a cult item. Equally important, Reprise believed in both her and her single, "Midnight at the Oasis" (written by her excellent guitarist David Nichtern), and fought for it long after another company might have given up. The results: It has broken as a national hit, insuring the continued growth in popularity of the album, as well. And it's an album that lasts. Like Ry Cooder, Maria Muldaur has found just the right balance between her commitment to the traditional material she favors and her ability to interpret it in a personal way.

- Jon Landau, Rolling Stone, 6/6/74.

Cut by cut, this bid to contemporize Maria's nouveau-jug music (two songs each from Wendy Waldman and David Nichtern, one each from Dr. John and Kate McGarrigle) is intelligent and attractive. But the overall effect is just slightly aimless and sterile. Maybe it's Muldaur's quavery voice, which only rarely has driven me to attention, or the low-risk flawlessness of the Lenny Waronker/Joe Boyd production. Or maybe it's just the curse of the jugheads -- not knowing how to make good on your flirtations with nostalgia. B+

- Robert Christgau, Christgau's Record Guide, 1981.

Further reading on Super Seventies RockSite!: |

- Lawrence Gabriel, Musichound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, 1996.

Maria Muldaur's solo debut appeared in 1973, during a moment of great openness in popular music. How open? The onetime folksinger gathered a Jimmie Rodgers country tune ("Any Old Time"), an introspective pop ballad (Ron Davies's "Long Hard Climb"), a saucy bit of cabaret ("Don't You Make Me High"), an evocation of old-timey entertainement ("Vaudeville Man"), and some sly passionately sung funk ("Three Dollar Bill"). And she put them all together, side by side, on the same album. And that album became a hit. Today, such a prospect might not survive ten minutes in a major label conference room.

Of course a big part of the album was "Midnight at the Oasis," the album's surprise single. Added after everything else was recorded, the tune is a flirty invitation to forbidden pleasure, set in an Arabian Nights desert. A breezy concoction, it falls somewhere between jazz, pop, and cocktail hour. Muldaur sings it like she's goofing around; she delivers lines like "Let's slip off to a sand dune and kick up a little dust" with a knowing wink. The musicians around her pick up on that pleasure-chasing vibe: After one of Muldaur's verses, guitarist Amos Garrett sneaks into the front of the mix with coy, pitch-bending chords and tasteful intimations of the blues. Many students of record-making, including Stevie Wonder, consider this one of the great instrumental breaks in all of pop.

The album is strong all the way through, and considering how many styles it visits, feels remarkably unified. Some credit for that goes to producers Joe Boyd and Lenny Waronker and the band, which includes pianist Mac Rebennack (Dr. John), mandolin wiz David Grisman, jazz bassist Dave Holland, and guitarist Ry Cooder. That's not to underplay Muldaur's role: She slides into these plusch, easygoing surroundings, and in a voice that's warm and untroubled and free of contrivance, spreads sunshine. While kicking up a little dust.

- Tom Moon, 1,000 Recordings To Hear Before You Die, 2008.

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.